What if doctors could tell you decades in advance whether you’re likely to develop lung disease? Researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus are working to make that idea a reality.

Dr. William Vandivier, a professor in the pulmonary division at CU and director of UCHealth’s Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) program, is leading a study designed to identify those at risk for COPD long before they develop symptoms. The research could change how doctors approach one of the most common and deadly respiratory diseases in America.

“It can take 20 or 30 years to develop disease if you smoke cigarettes,” Vandivier says. “We really have no idea who’s going to get it until they do. A lot happens in the lung in that 20 or 30 years – things that you don’t want to have happen. It would help us if we could understand what happens really early in the disease, so we might be able to prevent it or treat it better.”

The study, called the Airway Progenitor Dysfunction Research Study, is seeking current smokers aged 30-50 who have smoked for more than 10 years but haven’t been diagnosed with lung disease. Researchers are looking for over 100 participants from the Denver area, with some volunteers traveling from as far as 100 miles away. The study covers travel costs for those coming from a distance, procedures are provided at no charge, and participants receive compensation for their time.

The research is part of efforts at CU Anschutz to understand COPD in its earliest stages and develop better prevention and treatment. The goal is to develop a test that can predict who will develop COPD well before symptoms appear, similar to how cholesterol tests can predict heart disease risk. “It’s similar to how you’d find somebody who has evidence of high blood sugar and say, ‘If we don’t get this under control, then you’re going to have diabetes someday.’ We want to do that for lung disease,” Vandivier says.

Over the course of the study, pathologists examine biopsies from participants’ airways. By comparing these samples to changes in lung function, and CT scan findings over several years, they hope to identify groups of people who respond differently to high-risk conditions like smoke exposure.

COPD affects millions of Americans, causing breathing difficulties and chronic cough, among other symptoms reducing quality of life. The national lung disease problem goes beyond what most people realize. “About half of lung disease is caused by smoking, and about half of lung disease happens in people who have never smoked,” Vandivier says.

Vandivier and his team have discovered something surprising: many people who don’t meet the clinical criteria for COPD still have significant respiratory problems. In studies of flight attendants who were exposed to heavy secondhand smoke before smoking was banned on planes, roughly 20 percent developed diagnosable COPD. But among those who didn’t reach COPD criteria, about one-third still had chronic symptoms severe enough that treatment guidelines would recommend medication if they were smokers with COPD.

“I didn’t expect a third of people that don’t have diagnosable disease to have a major problem,” Vandivier says. “We identified someone 10 years ago who had normal lung function that didn’t meet the criteria for COPD, and she came back to see me clinically 10 years later, and she’s got full-blown COPD without smoking a bit.”

This discovery has led to a new medical classification: ‘pre-COPD,’ which describes people with chronic respiratory symptoms but lung function that doesn’t yet meet the technical criteria for COPD. The condition is now being included in clinical guidelines, and pharmaceutical companies are starting trials that target these populations. “It’s changing the future,” Vandivier says. “That’s good, because I think a lot of these people would not be seen if they don’t fit into a category where a clinician can say, ‘Yes, this is the label for what you have.’”

The key to predicting COPD, according to Vandivier’s research, lies in airway progenitor cells: cells that line the airways and repair damage when the lungs are injured. In healthy people, they heal the airways normally, but in people who develop COPD, progenitor cells fail at their job. When Vandivier’s team studied flight attendants who had been exposed to secondhand smoke decades earlier, they found that those with low progenitor cell function experienced faster lung disease development compared to those with normal progenitor cells.

“If we could have done this for somebody who’s in their 20s or 30s getting this exposure, we could potentially identify people that have a high risk of developing COPD symptoms down the line,” Vandivier says.

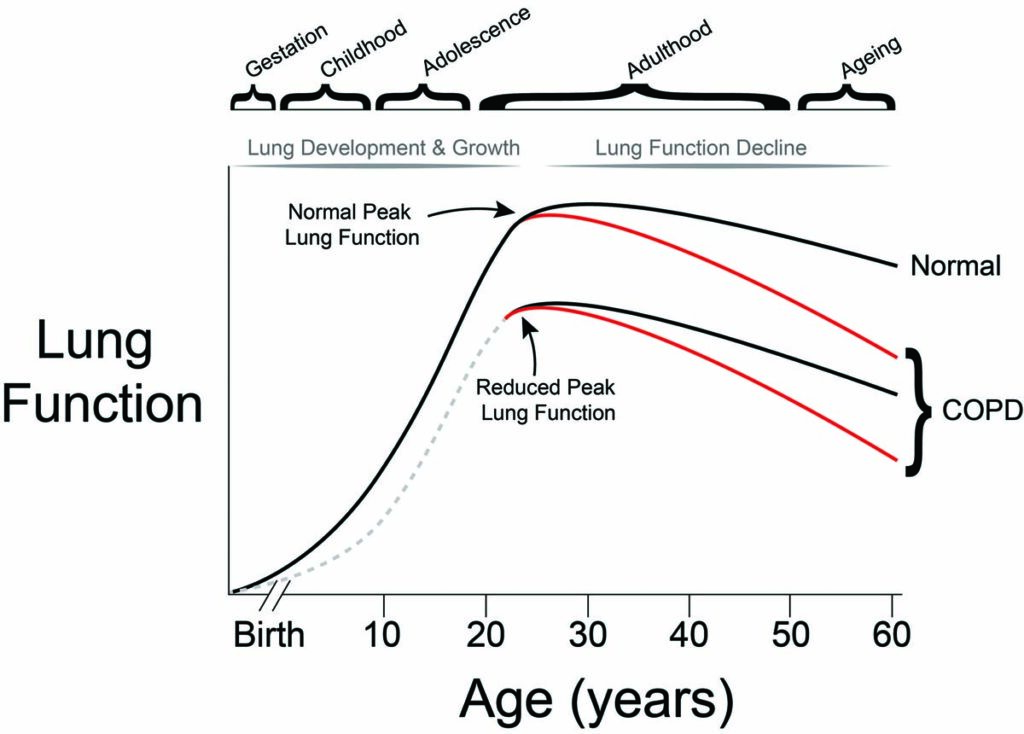

The timing of exposure matters significantly. “The lung develops in gestation at a really vulnerable time,” Vandivier explains. “During childhood, adolescence, early adulthood – the lungs continue to grow during that period of time, so they’re really vulnerable to outside factors.”

CU Anschutz researchers are already finding evidence of early COPD in study participants. “We’re finding people with emphysema or lung nodules that they didn’t know they had,” Vandivier says. “And others in the study have lung function that’s abnormal, but wouldn’t give a diagnosis of COPD.”

One of the complications in studying COPD is that it’s not one disease, but a syndrome with a variety of causes and traits. Some people reach peak lung function in early adulthood and then experience rapid decline, while others never reach peak lung function at all, especially if they’re exposed to risk factors during childhood. “Most people who have COPD related to exposures like secondhand smoke don’t ever reach proper lung function,” Vandivier says.

COPD symptoms vary widely, so it’s difficult to make a full diagnosis based on symptoms alone. “Most people with COPD get a cough, and eventually shortness of breath,” Vandivier explains. “But they might lose some energy, or might not, and depending upon where they are, they might have flare ups all the time. You can’t tell just based upon symptoms what’s underlying them. That’s why you have to get at the biology and the trajectory over time to try to really understand what’s going on.”

The current study is funded through 2028, with a possible extension to 2029. If the research yields promising results, Vandivier hopes to continue following participants for even longer periods. The longer the study continues, the clearer the patterns become, especially with a relatively small group.

Vandivier and his team also hope to expand their work to study people exposed to secondhand smoke during childhood and early adulthood. That project is currently awaiting funding approval.

For now, the focus is on recruiting local smokers who want to learn more about their lung health. The study offers participants testing they wouldn’t normally receive, along with the knowledge of whether they’re showing early signs of disease.

“We want to be able to tell patients, ‘You don’t have the disease yet, but you are one of the vulnerable people who are highly likely to get it if you continue down this pathway,” Vandivier says.

For those interested in participating or learning more about the Airway Progenitor Dysfunction Research Study, contact the Vandivier Research Team at 303-724-6067 or email [email protected].