Whether you call it gastroenteritis, the 24-hour flu or Montezuma’s Revenge, food poisoning can be miserable, ruin a perfectly nice weekend, and in some cases, land you in the hospital. Forty-eight million people suffer from a food-borne illness in the U.S. each year. Of these, 128,000 people are hospitalized and 3,000 die according to the CDC. Recent outbreaks include Listeria in deli meats, E. coli in organic carrots and in onions served at a popular fast-food restaurant, and Salmonella in cucumbers and eggs. Food poisoning is a common and largely preventable public health problem. But how is it acquired, who is at risk, how do you know if you have food poisoning, and how can it be prevented?

There are numerous pathogens (bacteria and/or their toxins, viruses, or parasites) that can lead to food-borne illness. Food can become contaminated at any point during the production process involving the distribution or preparation phases in our food production chain. Improper handling, preparation, and storage are the top reasons for food contamination and potential illness.

Norovirus is the most common food-borne illness. It is highly contagious, easily transmitted and often associated with family or community-wide outbreaks of food poisoning, especially in the winter. However, Salmonella is the most common cause of gastroenteritis leading to hospitalization and death.

People with a weakened immune system are more vulnerable to food-borne illnesses. This includes people under age 5, over sixty-five, pregnant women and their unborn babies, people with chronic disease, such as diabetes or cancer, and those who take medications that suppress the immune system.

Although rare, pregnant women are ten times more likely to get Listeriosis from Listeria infection than the general population. Listeriosis may result in early miscarriage, premature labor, low birth weight, as well as impairments of baby’s brain, heart, or kidney. In some cases, it can result in death of mom or baby.

Common symptoms of food-borne illness are diarrhea, stomach pain or cramps, nausea, vomiting and sometimes fever. The onset of symptoms can be from hours to weeks depending on the offending organism or toxin. Improvement or resolution may occur in a few days without any intervention. However, it is imperative to seek medical care if symptoms persist, are severe, or include bloody diarrhea, a fever above 102°F, intractable vomiting and signs of dehydration (thirst, little or dark urine, lethargy, dizziness when standing) or if you experience numbness, vision changes or paralysis.

Treatment is generally supportive. Stay hydrated, rest, and when hungry again, eat bland food such as the BRAT diet: bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast.

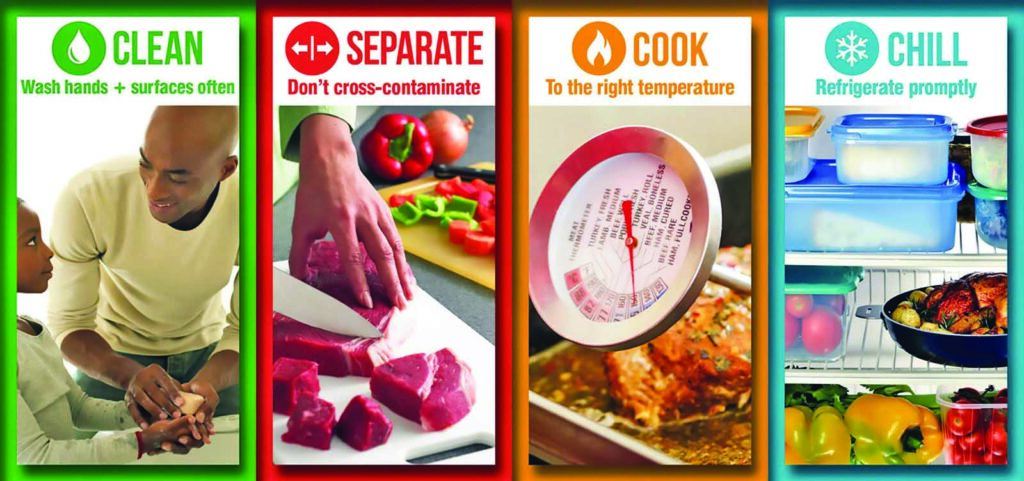

Food poisoning is more likely to occur when consuming food prepared at home. Safe food storage and preparation are the most important measures to prevent food-borne illness. The CDC recommends Clean, Separate, Cook, and Chill when preparing food and includes the following general guidelines:

- Always wash your hands and work area with warm, soapy water before preparing food and after using the facilities.

- Avoid cross contamination by keeping uncooked foods like meat, poultry or fish/seafood separate from foods that are sometimes eaten raw, such as vegetables or salads.

- Wash produce in clean running water before eating, cutting, and cooking.

- Check the internal temperature of meat, poultry, and seafood/fish to make sure they are cooked properly.

- Cook eggs until yoke and white are firm.

- Do not leave food out at room temperature for more than two hours, or for more than one hour when the temperature is 90°F or higher.

- If pregnant, do not eat unpasteurized dairy products, deli meats, soft cheeses, refrigerated pâtés or smoked fish due to Listeria risk.

- Do not prepare family dinner if you are sick.

Safe and happy holidays from all of us at Intermountain Health Lutheran Hospital.