The technical aspects of art aren’t what most of us are considering when we attend an art show. Fundamental aspects aren’t as glamorous as the aesthetically effective renderings that may be created by using them. We’re just there for the art. But without the underlying science of pigment, there would be no “magic.”

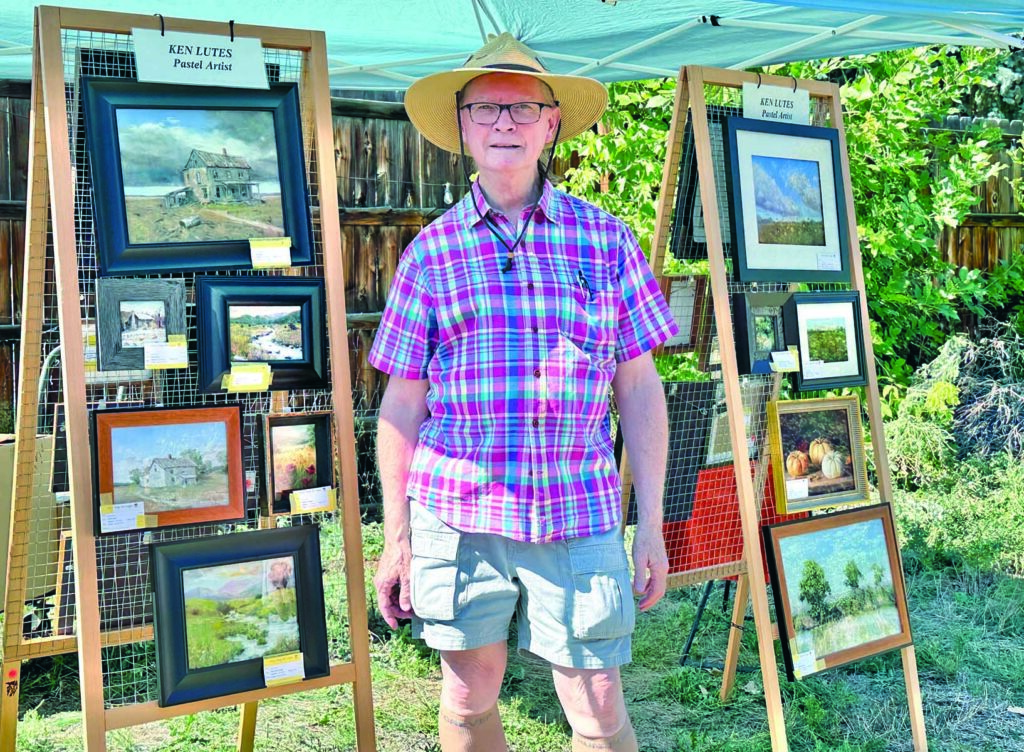

Art on the Farm gives us the opportunity to enjoy the magical renderings created by a collective of artists who paint with acrylics, oils, watercolors, inks and pastels. Here, artists display their colorful works along a narrow three-block-long band of land accessible from 38th Avenue, just off Ward Rd.

The environment is farm-like, with clusters of vegetable gardens and a coop of several chickens scurrying inside it. But the ambience is of the art, often permeated by the sound of live music. This summer, some artists set up displays under 10’x10’ tents, and several artists painted en plein air, the centuries-old tradition of painting outdoors. An artisan set up a small letter press and printed custom postcards.

These works of art might seem on the surface to be disparate and diverse, but they have one very important thing in common, and that is pigment.

Pigment is a substance, which when combined with a vehicle such as water or oil, imparts color. Black or white or colored paints derive from pigments. Dyes are sometimes used, but pigments provide a solid base for binder reactions, resist ultraviolet light, and create a stable coating for surfaces. Pigment-based colors are generally more opaque than dyes and more resistant to fading.

Artist Ginger Davis Allman says the difference between pigments and dyes “boils down to mud vs. sugar.” She explains that a cupful of muddy water scooped from a puddle colors the water brown and, given enough time, the dirt particles will settle to the bottom, leaving the water relatively clear. Iron oxides and ochres—many reds, yellows, and oranges—to this day are quarried to make pigment.

On the other hand, Allman said, “if you mix a spoonful of sugar into a cup of water, the sugar will completely dissolve in the water.” Our ancestors made dyes from berries, roots and flowers.

“I made paints using marigolds,” says local artist Judy Miranda, known for her retablos that are painted on carved wood. “But those colors do fade.” She told a story of a time in New Mexico when a weaver advised her to find an old railroad spike and let it oxidize in her paint, that the rust would give her the more permanent color she was looking for. “And it did.”

Oil paint is perhaps the most revered medium in the art world, used by the greatest painters of all time. Oil paints are created when dry pigment is combined, most commonly, with cold-pressed linseed oil (the binding agent), but sometimes walnut oil or poppy oil. Colors can be easily mixed, and, because of oil’s slow drying time, they may continue to be blended over many days. The downside of using oils is that it can take months for the paint to dry, and solvents needed for brush cleaning and paint thinning can be toxic.

Painting with acrylics can be both a blessing and a curse. Acrylics consist of pigment mixed with an acrylic polymer emulsion (the binder). Water is the vehicle for this type of paint, and it can quickly dry by evaporation, yielding a much shorter working time than with oils. As with oils, a range of texture can be produced with acrylics. Adhesion is excellent, and the colors are vibrant. The costs are typically lower than for oils, and clean-up is done with water.

Watercolors may be admired for their delicate, transparent nature. A water-soluble binder, such as gum Arabic, is used to hold together the pigments and allows the pigment to adhere to a painted surface, usually paper. Watercolors dry quickly and correcting mistakes can be challenging.

Pastels have a higher pigment concentration than any other medium and therefore produce intense, rich colors. The writer of this article is a pastel artist and makes his own pastels from pure pigments. He paints with dry pastels in stick form, as opposed to oil pastels. Some pigments he uses to create pastel sticks come from a quarry in France and are combined with a solution of methylcellulose (binder) and a preservative (forestalls mold) to create the colors used in his paintings. Some colors may contain toxic pigments, and care is taken to minimize dust dispersion.

As with watercolors, finished pastels must be protected by glass.

The development of pigments and the technology used to create them has influenced the history of art since its earliest forms, when perhaps mud slung against a cave wall created the first painting.

Over time, artists began to discern the variety of colors inherent within natural materials. For example, the blue stone lapis lazuli was ground into a powder that we now call ultramarine blue.

Each artist creates from technology the expression of their creative vision using either oils, acrylics, inks, watercolors or pastels. The underlying, scientific agent they all have in common is pigment.

When you visit Art on the Farm next year—or any art show between now and then—please stop and talk with the artists about their art and the technical aspects of their work.

PHOTOS BY TOMMY KILPATRICK

Art on the Farm: From My Perspective

By Natalia Hites-Cotroneo

On September 28th, I attended Art on the Farm, a community event in Wheat Ridge that showcased artists of all kinds. Held in the expansive backyard of Guy Nahmiach, surrounded by produce grown on his own farm, and chickens in the chicken coop, this event brought together local artists, musicians, and community members to celebrate creativity and connection. I saw firsthand how local artists from my neighborhood came together to share their incredible work.

Not knowing what to expect, I walked onto the farm and was immediately struck by a sense of community. The relaxed outdoor setting offered the perfect opportunity to meet new people while exploring the impressive artistic displays. Art on the Farm was a wonderful reminder of how art in all forms can bring people together, spark meaningful conversations, and create a sense of belonging.

One of the artists who stood out to me was Kathleen Martell, Chair of the Wheat Ridge Cultural Commission. She explained her creative process, using old parts to weld figurines, and shared how historical women inspire many of her pieces. Listening to her creative process and the story behind her pieces added an even deeper meaning to the event. She showed how art can connect the past and the present, and tell stories in the process.

Another memorable artist was Terry Womble, who demonstrated his use of paint in a unique way that immediately captured my attention. By using thick globs of paint that dried in raised textures, Terry’s work had a mesmerizing effect, drawing me in for a closer look. His tactile and innovative approach to painting offered a fresh take on traditional techniques and left a lasting impression.

In addition to these artists, there were a variety of painters doing live demonstrations at the festival as well. Each brought a unique perspective to the community. The diversity of the artwork, and the talent on display was remarkable. The live band played upbeat, energizing music that resonated throughout the event, keeping the crowd entertained, and adding to the enjoyable atmosphere.

The event also featured a raffle, with a beautiful painting and an easel. The raffle added an element of excitement and the hope of taking home a piece of the event. This, along with the art itself, helped make Art on the Farm, an event to remember.

Overall, Art on the Farm was a vibrant celebration of local art in Wheat Ridge, and I felt so inspired by the creativity of the artists and the joy of the community. I met a lot of people that I would normally have never met. Most importantly, this event reminded me of the power of community and the need to foster connection and support for one another.